How did you get interested in Polaroid?

I always liked instant pictures, and a few early memories leap to mind. The Pronto! SX-70 camera we bought my dad around 1980, as (I think) a Father’s Day present. The Square Shooter 2 that my grandmother owned. My own first instant camera, a secondhand Model 900, bought for $3 when I was about 13. The subsequent twenty minutes I spent on the phone with a patient customer-service rep at Polaroid, as she walked me through how to use that camera and change the batteries. Mostly, I got the bug the same way everyone does: staring into the gray-green mist of a Polaroid picture as it develops. It’s a bewitching thing. And I have always been interested in outlier technologies, especially when they become rare and precious.

How did that lead to a book?

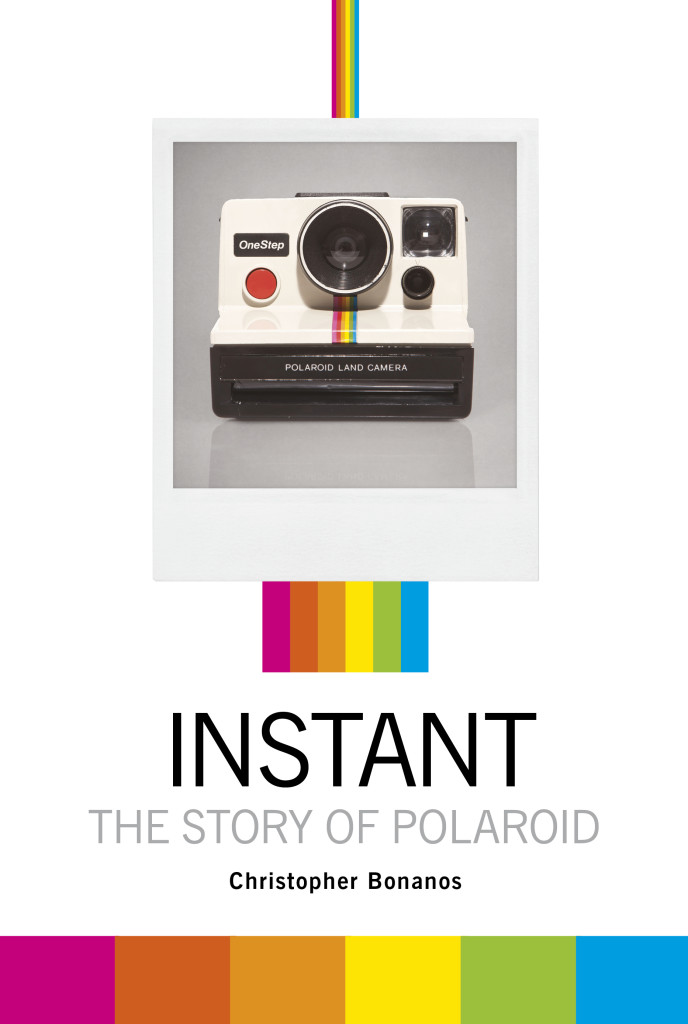

In 2008, the Whitney Museum of American Art was about to open a show of Robert Mapplethorpe’s Polaroid photographs. Since I edit New York magazine’s art coverage, I got a call from Stephen Soba, a friend in the press office of the Whitney, suggesting a little feature on it. I had just heard that Polaroid was quitting the instant-film business, and had the idea of doing a story about the coincidence of these two events, so I called a couple of prominent photographers to see what they had to say. It turned out that they were all furious to see a great artistic material disappearing for reasons that had less to do with obsolescence than with greed. By the time the story ran, I had discovered savepolaroid.com, and started to get sucked in. A few months later, I had a book proposal written and an agent (the hardworking Kris Dahl, of ICM) circulating it. It was a tough sell in the awful business climate of 2009, but here we are. I am delighted that Princeton Architectural Press, which produces gorgeous books about design, photography, and art, said yes. Special props to Nicola Bednarek, who acquired the book, and Dan Simon, who took it over last year and is editing it.

How did you research it?

Dozens of phone interviews, plus a whole bunch of time spent in Harvard Business School’s Baker Library, which houses Polaroid’s archives. Because of concerns about patent primacy, Polaroid was manic about record-keeping; the policy seems to have been “save everything, and get it signed and dated.” In 2004, the company gave the whole heap (millions of pages of documents, and millions of photos, as well as tapes, records, videos, and just about every other kind of media) to HBS, where it is being slowly put in order by a staff of librarians, headed by a diligent guy named Tim Mahoney. The Polaroid archive was perhaps 15 percent sorted out when I was there doing my research, with many years to go. (This project is likely to occupy the majority of Tim’s career.) I did not take a leave of absence from my job—I did this all on weekends, during the evenings, and with vacation time—so I had just a few frantic weeks at Harvard, reading and taking notes at top speed; fortunately, Baker Library allows researchers to work with a digital camera, so I often found myself snapping away, then reading the pages at home later on, to get the most out of my time there.

Any other books?

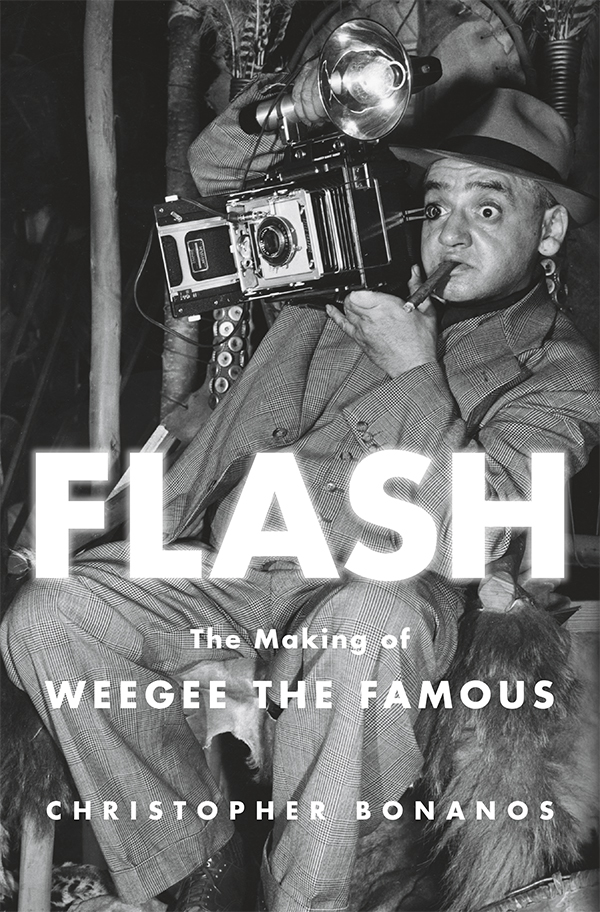

Why, yes—glad you asked. In 2018, I followed that one up with with Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous, the first biography of the great New York photographer Arthur (Weegee) Fellig. It was reviewed in The New Yorker, The New York Times (and again on Sunday), The New York Review of Books, and lots of other places; it also won the National Book Critics Circle Award for best biography of 2018, an honor that I still cannot believe. You can read an excerpt here.

Long ago, I also wrote a tiny little book of essays about Greek-American culture, And I’ve written essays for this catalogue that accompanied a Polaroid exhibition, and four great graphic-design handbooks from the 1970s that have been lovingly reissued by Standards Manual LLC.

Can you still get film for a Polaroid camera?

Depends on your camera, but sometimes the answer is yes. Lots more about that here.

I have an old Polaroid camera. Is it worth anything?

In most cases, not much. It’s an issue of supply and demand: Polaroid photography was extremely popular, and there are a lot more cameras than there are people who want them. Exceptions are the professional models and the folding leather-covered SX-70 cameras, which each have small but intense followings. The most valuable cameras are the Model 180, 185, 190, and 195, which were marketed to professionals and have manual controls and good lenses. They typically sell in the $400-to-$500 range today, though you may luck out at a yard sale sometime.

The following models are also worth significant amounts to photographers and collectors:

SX-70 folding cameras (about $50 to $150, depending on condition and particular model)

SLR 680 and SLR 690 folding cameras (about $200, sometimes more)

Model 110/110a/110b (about $50 to $100; significantly more if they’ve been converted for today’s film)

Automatic 100/250/350/360/450 ($40 to $60; more if they’ve been reconditioned)

Most others, I’m sorry to say, are in the under-$20 range. (Your best real-world price guide is probably the Completed Auctions section of eBay.) They make nice decor, though. A friend of mine has a few lined up on her mantelpiece, and they look awesome.

Where can I learn more?

I’ve put together a basic guide to making instant pictures today here. There is, however, far more to read at the two principal Web depositories for Polaroid information. The Land List is a very old site (1993!), and it needs some updating but is still extremely useful. Instant Options goes it one better, incorporating the Land List’s data and bringing it up to date, and offering additional how-tos and news. Its proprietor also offers repairs and camera conversions (adapting old cameras to take film that’s available today, among other things), and I can tell you that the man knows his shutters. You can also learn more at Flickr’s Polaroid discussion group.

Who built this Website?

The charming, funny, and extremely talented Katie Van Syckle. She was, at the time, a freelancer who was getting her journalism career off the ground, constructing Websites and waiting tables on the side to make ends meet; less than a decade later, she is a big deal at the New York Times. We in Polaroidland are delighted to have watched her fast-track climb.

LEGALITIES

This site is not connected with or endorsed by Polaroid or PLR IP Holdings, owners of the Polaroid trademark.ON TWITTER

My TweetsBlogroll

- 'Insisting on the Impossible'

- Everything Reminds Me of You

- Flickr's Polaroid group

- Instant Options

- LandCameras.com

- Paul Giambarba: Analog Photography At Its Best

- Paul Giambarba: The Branding of Polaroid

- Polaroid

- Polaroid SF

- Rare Medium

- The Impossible Project

- The Land List

- The New55 Project

- Vintage Instant